Paper or Digital? — a Research Review

Does one media type help or hinder human cognition in academia?

Abstract

As current and future decades of students immerse themselves into social sciences, history, mathematics, and languages alike, one might ask how will they be met by technology to enhance these experiences? This research review looks into student’s comprehension with respect to using e-readers (iPad, Kindle, etc) and conventional paper books in elementary/middle, secondary, and university academics. The findings with this review have shown that conventional textbooks are still the viable choice amongst students in all levels, most notably university students. Device distractions and limited human interactions with e-readers are not easily avoidable, therefore causing an overtaxed memory with mental and physical fatigues.

While many use an e-reader for casual reading and enjoy the experiences that accompany the device, academic organizations are still trying to introduce these same devices into present day academia. Contrary to the technological push for e-readers, a recent analysis shows trends in “children’s books to adult non-fiction paper book sales went up 2.4% in 2014 which includes online retailers like Amazon and all types of bookstores” (Catalano, 2015, para. 3). In addition to casual reading, “students in several studies have found a strong preference for printed textbooks, notably those in college who have tried both types” (Catalano, 2015, para, 5). With U.S. e-books hovering around twenty-five percent of all books purchases, why is academia not contributing more to this growth?

While digital publishers market their e-book technology and accompanying prices make it an ideal reason for making the purchase, researchers still investigate reasons why academia does not embrace the digital library of e-books. Hillesund (2010) described continuous reading as the ability to read from beginning to end, similar to the way a reader engages in a novel. He also describes discontinuous reading as nonlinear and fragmented, the readers’ eye movements skim and move back-and-forth looking for cross-reference material. These styles of reading and their user experiences during the reading process create cognitive maps that allow the reader to embrace both human cognition and their academic goals.

Elementary / Middle

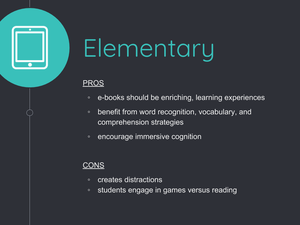

Young readers take advantage of digital technology everyday. The Digital Textbook Collaborative (FCC, 2012) publishes a guide for designing enriching, digital learning experiences. This document outlines digital textbooks as offering “rich, interactive learning experiences, personalize learning, encourage collaboration, provide feedback, and support formative assessments as well as student self-assessments” (Dalton, 2014, p. 38). Students who benefit from the activities of e-readers show that embedded multimedia helps support “word recognition, vocabulary, and comprehension strategies” (Dalton, 2014, p. 39) all of which encompass ideals of the guide. Interactive e-readers, unlike textbooks, allow students to proactively read and/or listen to a storyline. The multimedia activities like animation, sound, and visualization contribute to solidifying a young reader’s overall comprehension, vocabulary, and understanding of key concepts. These enhancements of e-readers contribute and reinforce the written text, all while aiding the reader in immersive cognition.

Contrary to the benefits of learning with e-readers, studies show that younger student’s attention and amounts of recallable comprehension may be degraded. Schugars et al. (2013) research finds the “richness of the multimedia environment that e-books provide - heralded as their advantage over printed books - may overwhelm children’s limited working memory. The overworked memory may lead to narrative loss or the processing of the story less deeply” (Paul, 2014, para. 5).

The multimedia enhancements of e-readers create distractions, which interrupt the student’s ability to fully comprehend the subject matter. Schugars et al. (2013, p. 618) research suggests that many of the distractions identified were focused more on device usability instead of the actual school work. In addition, educators assumed their students previous working knowledge of the device was performed under parental guidance. Parent-child interactions with e-readers is found to focus more on the skills needed to interact with the technology, like swiping to turn a page, than the actual content (Schugars et al., 2013, p. 618). Students who use e-books were found to have engaged in playing games versus reading the actual text forty-three percent of the time (Schugars et al., 2013).

In addition to the distraction of multimedia scattered throughout the text, Schugars et al. (2013, p. 619) suggests that while reading e-books, students were not observed using typical reading behaviors like bookmarking, annotating, or highlighting. These actions which help facilitate reading strategies like summarizing and determining main ideas are typical byproducts of reading paper books.

Secondary

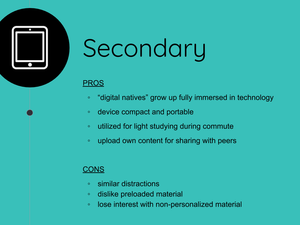

Research has a common misconception that “digital natives - a younger generation of people growing up fully immersed in the advent of digital technologies and computer networks” (Cheng, Y.-C et al., 2013, p.17-18) have been blessed with a proficiency of user experiences which was not previously available to past generations. While most studies focus on screens versus tradition paper, one study by Cheng et al. (2013) examines previous digital media usage. Researchers distributed customized e-readers to selective students for a duration of five months. During the study, every student’s interaction with the device was collected and analyzed.

Cheng et al. (2013) findings showed little to no initial indication of difficulty in using the device other than some complaints of slow page response. While a majority of the students explored the devices’ features (text, music, photos, etc) many of them found the device to be “‘cool,’ ‘lightweight,’ and ‘convenient’ ” (Cheng et al., 2010, p. 23). A survey administered weeks later reveals that most students were not interested in the preloaded textbooks or course curriculum. Rather, they prefer to load their own media files to the device.

Additional survey results identified that students found “portability and convenience to be the most favorable traits” (Cheng et al., 2010, p. 23) of the device. Even though these traits were impressive, the quantitative data identified a majority of the students as inactive users due to loosing interest in the device. The remaining students were either casual users with online activities like discussion boards, forms, and questionnaires; or very active users with little online activity. The group of very active users identified by Cheng et al. (2010, p. 25) could be categorized into three classes, “reading-oriented — user spends time reading content not on device’s operations, operation-oriented — user spends majority of time operating the device and skimming through content, and hybrid — user spends time between the two extremes.”

Research from Cheng et al. (2010) discovered that a majority of students primarily found the device good for memorization or extra-curricular reading. These actions come from the device’s high marks of portability; because students prepare for exams or leisurely read during their daily commute. In addition, students find searching for online content and the ability to share it with friends (Cheng et al., 2010, p. 30) to be encouraging and inspirational as they consider Internet access a staple function in their day to day life.

University

University students find e-readers great for their needs with portability, convenience and additional features like legibility of text, extendable storage, and wireless connectivity, but the presence or absence of specific functions make it very troublesome (Thayer, 2011). Thayer (2011, p. 2918) identifies academic reading as involving a variety of special tasks and reading objectives.

For many students it is not just about reading content, but preparation, research, and information. Higher education reading is related more towards “academic-specific goals” and not just “personal choice” (Thayer, 2011). Research suggests that students embrace e-reader technology, but the methodologies of “scanning, search reading, skimming, receptive reading, and responsive reading” (Pugh, 1978) create ineffective study patterns. The outcome of these comprehensive practices allows for critical information to get lost, which in turn requires the student to reread previously missed content (Services, 2014). Therefore, students feel dissatisfied with the device’s technological features which hinder their engagement in active reading and inability to form comments, highlight text, annotate, perform nonlinear reading, locate illustrations, and explorer inline references (Olsen et al., 2013; Thayer, 2011).

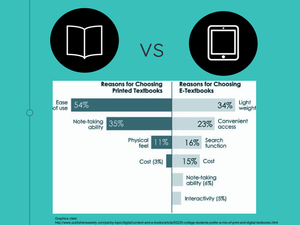

Since university students consider these tasks critically important to their overall reading practices, many of them, according to Carr (2013), believe that traditional paper books are superior for studying and academic success. Students find that textbooks carry fewer distractions and temptations like email, Facebook, notifications, and unrelated information. In addition, students feel activities like highlighting or marking text are a more effective way to retain subject matter (Carr, 2013).

While Margolin’s et al. (2013) research identifies human interaction with textbooks, it highlights traditional reading behaviors like following along with a finger, moving lips, dog-earring a page, or grabbing a pen/highlighter to mark words (Catalano, 2015). Whether a university student is simply preparing for lectures, studying for exams, taking notes in class, or utilizing the device’s portability for group work, students are using a device to accompany their academic goals. These students may not be using the device exclusively, due to its technological shortfalls, but they are certainly creating a hybrid approach with traditional paper books.

Conclusion

Measuring technology’s influences on traditional academic methodologies through e-readers has uncovered that students still prefer paper textbooks. With increasing educational demands on our working memory and the pursuit of e-readers by academia, students describe their study habits as creating more physical and mental fatigue. While a leisure reading experience may be quicker and more enjoyable on an e-reader, a student’s academic goals are achieved when human factors of reading are engaged with traditional textbooks. Tasks involved with figuring out device navigations and other distractions that accompany using the device, may limit or hinder comprehension of the material. Therefore, “students engage more deeply with printed textbooks, and prefer print for sustained in-depth reading” (Tan, 2014).

References

Carr, N., (2013, February 20). Students to e-Textbooks: No Thanks. Rough Type. Retrieved from http://www.roughtype.com/?p=2922

Catalano, F., (2015, January 18). Paper is back: Why ‘real’ books are on the rebound. GeekWire. Retrieved from http://www.geekwire.com/2015/paper-back-real-books-rebound/

Cheng, Y.-C., Liao, W.-H., Li, T.-Y., Chueh, C.-P., & Cho, H.-C. (2013, January 01). Exploring the Reading Experiences of High School Students on E-Book Reader. International Journal of Online Pedagogy and Course Design (ijopcd), 3, 1, 17-32.

Connell, C., Bayliss, L., & Farmer, W. (2012, June 01). Effects of eBook Readers and Tablet Computers on Reading Comprehension. International Journal of Instructional Media, 39, 2.)

Dalton, B. (2014, January 01). E-text and e-books are changing literacy landscape. Phi Delta Kappan, 96, 3, 38-43.

Digital Textbook Collaborative. (2012). Digital textbook playbook. Washington, DC: Federal Trade Commission. Retrieved from http://www.fcc.gov/encyclopedia/digital-textbook-playbook

Hillesund, T. (2010). Digital reading spaces: How expert readers handle books, the Web and electronic paper. First Monday, 15(4). Retreived from http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/viewArticle/2762/2504

Howard, J., (2013, January 27). For Many Students, Print is Still King. The Chronicle of Higher Learning. Retrieved from

http://chronicle.com/article/For-Many-Students-Print-Is/136829

Margolin, S. J., Driscoll, C., Toland, M. J., & Kegler, J. L. (2013, July 01). E-readers, Computer Screens, or Paper: Does Reading Comprehension Change Across Media Platforms? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 27, 4, 512-519.

Olsen, A. N., Kleivset, B., & Langseth, H. (2013, April 02). E-Book Readers in Higher Education: Student Reading Preferences and Other Data From Surveys at the University of Agder. Sage Open, 3, 2.)

Paul, A.M., (2014, April 10). Students Reading E-books are Losing Out. The New York Times. Retrieved from

http://parenting.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/04/10/students-reading-e-books-are-losing-out-study-suggests

Pugh, A. K. (1978). Silent reading: An introduction to its study and teaching. London: Heinemann Educational.

Schugar, H.R., Smith, C.A. & Schugar, J.T. (2013). Teaching With Interactive Picture E-Books in Grades K–6. The Reading Teacher, 66(8), 615–624. doi: 10.1002/trtr.1168

Services, C., (2014, August 27). E-Textbooks Effectiveness Studied. Department of Psychology James Madison University. Retrieved from

http://www.psyc.jmu.edu/ug/features/etextbooks.html

Tan, T., (2014, July 8). College Students Still Prefer Print Textbooks. Publisher Weekly. Retrieved from

http://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/digital/content-and-e-books/article/63225-college-students-prefer-a-mix-of-print-and-digital-textbooks.html

Thayer, A., Lee, C. P., Hwang, L. H., Sales, H., Sen, P., Dalal, N., & 29th Annual CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI 2011. (2011, June 13). The imposition and superimposition of digital reading technology: The academic potential of E-readers. Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - Proceedings, 2917-2926.